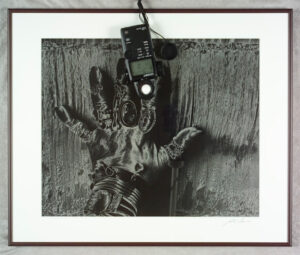

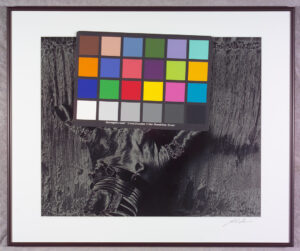

Beginning with this post I am going to make prints of some of the images on my blog available. More information is posted at the end of this blog. Thanks for your support

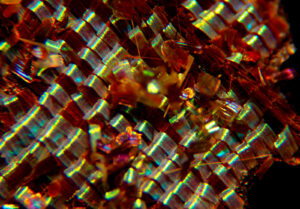

Watch face DSC-2184

In the book Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance the author (Robert M. Pirsig) quotes an instruction booklet, that said “assembly of Japanese bicycle require great peace of mind.” Macro and micro photography require that your peace of mind increase in direct proportion to the reduction in the size of the object you are photographing. It gets more difficult, and it requires more patience, as you get closer.

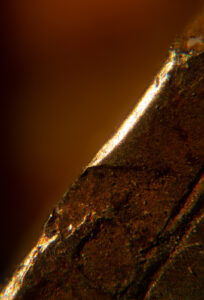

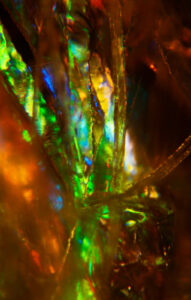

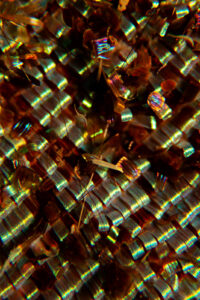

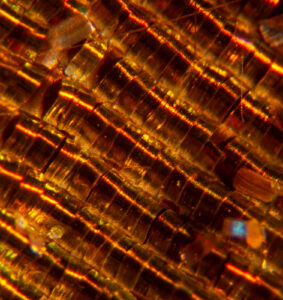

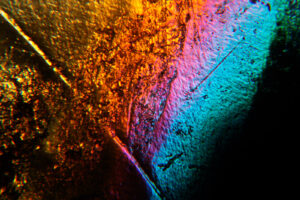

butterfly wing DSC-2184

Most people approach macro photography by purchasing some sort of macro lens which enables them to reproduce picture of an object at perhaps one quarter the size of the object in real life on the sensor of their camera, maybe even bigger. So, one quarter reproduction means that if you had a 25 cent piece, a quarter in US language, you could take a picture four of them and stacked across the short distance of a full frame sensor sensor. And they would fit. The quarter is an inch wide and a full frame sensor is an inch wide (and an inch and a half long). If the quarter filled a full frame sensor it would be a 1:1 capture, or life size.

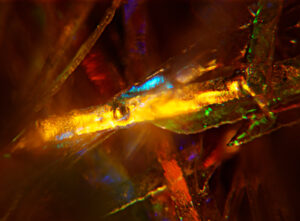

watch part DSC2146

Macro photography is occasionally discussed in terms of where it begins and where it’s simply a close-up. I’m not sure that that’s terribly useful, but, when you are less than three feet from your subject with a more or less normal lens, you’re pretty close and it isn’t necessarily difficult to make that picture, depending upon the equipment you’re using. As you get within less than an inch of your subject it gets to be extremely difficult to shoot, and when you are within one or two millimeters of your subject, it becomes almost impossibly difficult to photograph. What I’m going to explain here is photography with the microscope, which is generally photography within less than an inch of the subject.

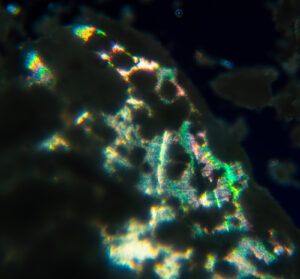

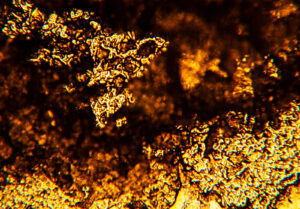

hair gel _DSC2073

I will discuss other ways of doing close-up work in other postings. This posting is concerned with very, very close microscope work. This is not the usual way I approach this subject: in the past I’ve discussed macro photography and built up to micro and microscopic photography. That might make more sense. However, I’ve recently posted a lot of photographs made with the microscope, and so I hope that many people might be interested if I start there.

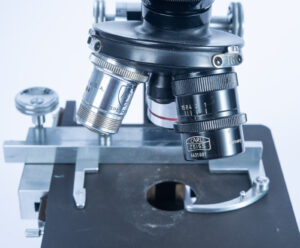

Leitz Microscope

The first thing about the microscope is to understand that the actual equipment that you need to do this kind of photography is easier to get, and less expensive, than you might think it would be. That’s important because one of the things I would hope that this discussion does is to encourage you to try this kind of micro photography or microscopy if you want to be more formal.

Leitz Microscope set-up

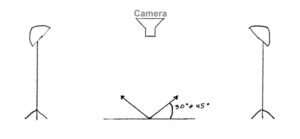

Before I write about the individual components of the camera/microscope combination, I’d like to give an overview of the set-up, from top to bottom. At the top is a digital SLR, the currently available cameras would be good for this. Next is a T-mount (more below) which connects the camera lens mount to a microscope adapter. This adapter is basically a hollow tube that fits between the camera and the eyepiece tube. The eyepiece is in the eyepiece tube, and it’s the first part for the optical system. The eyepiece tube is connected to the microscope head, where the lens or lenses are mounted. That lens is called the objective lens and it is the second part of the optical system. Below the objective lens is the stage, which is where you’ll place your subject. Under the stage there will often be an iris/condenser device, which can be used to change the quality of the light coming through the subject. Probably most scopes have a mirror below the condenser, but a few will have a light source. I think a mirror is more useful. At the bottom is the base, which is usually heavy to keep the whole thing stable.C14 The condenser, it helps to focus the light onto the subject

The large wheel is course focus and the small one is fine focus. They are often set up this way on modern scopes

The condenser, it helps to focus the light onto the subject.

A decent student grade microscope can be had for around a hundred and fifty dollars. This will do the job. Of course, you can spend much more on a microscope, but since you are not trying to accurately reproduce pictures of cell division or tiny crystalline structures (at least I’m hoping you’re not) a student grade microscope is a good choice. A student grade scope has course focusing and fine focusing, two separate knobs. It takes standard interchangeable eyepieces and interchangeable objective lenses with a standard thread. I’ll put a link to a student scope, and the rest of the stuff, at the end of the post.

Objective lenses on Lens turret

Eyepiece

In order to understand the reproduction ratio of a microscope for viewing it’s pretty simple. The eyepiece and the objective lens have numbers for their power, say 10x or 4x. Multiply the two numbers and you have the power of the system. So, if you have a 4X objective and 10X eyepiece, you would be viewing at 40 times life size, which is a nice range to work in. I’m not actually sure that this is exactly the power on your camera sensor, but whatever it is you’re damn close. When you make a print of the capture or reproduce it on your computer screen it gets larger still. So, you are frequently looking at things that may be a hundred, two hundred maybe even three hundred times life size on your computer screen, which is pretty impressive.

Microscope Adapter and T-mount

The adapters that you need to do this, in addition to the scope, are first a microscope adapter. This fits around the eyepiece tube on a standard microscope. Is available for less than $40. Surplus shed would be a good place to start looking for them. In addition, you will need a T-mount adapter. T-mount was an early interchangeable lens mount that is still used today. A T-mount lens could fit onto cameras with several different lens mounts, if you used the right adapter. And it remained unchanged and in use pretty much to this day. There are mounts for most current cameras, even mirrorless. T-mount is also used for telescopes and some other optical systems. You can also get old mirror lenses that use t-mount adapters. They can be a lot of fun. T-mounts are available from Surplus Shed and B&H Photo and any of a variety of suppliers.

The camera on top of the scope

Microscope and T-mount attached. They are screwed together

The microscope adapter is two pieces. It’s easier to mount the small piece on the scope and mount the larger piece onto the camera and then put them together on top of the scope.

You should start with the microscope arranged vertically. Most of the student grade microscopes, in fact, I think all of them, will tilt backwards to make it easier to sit and view your subject. Unfortunately, if you mount your camera on the microscope in this way, it will probably fall off the microscope and that would be a bad thing. So, you’ll set up the microscope vertically. Important safety tip. It is also very important to set the camera to use the self-timer. If you trigger the camera directly with the shutter release you will shake the camera and get fuzzy pictures. You could also use a remote release, but the self-timer works very well for microscope work.

Microscope lenses- Shown are a 4X Plan, a 25mm Zeiss Luminar and a Spencer 10X. This is the group I’ll usually put onto the scope.

I would always start with a 4X objective lens. I say this because one of the problems that you’ll get into, as I mentioned earlier, is the closer you get to your subject the more difficult it is to manage taking a picture of the subject. With a 4X objective lens, the lens will end up being between a quarter and three-quarters of an inch from your subject. That gives you just enough room to light the subject from above. It also gives you room to put a filter on the lens; it gives you room to do a whole lot of things. A 10X lens will be less than 3 millimeters from your subject, which makes it impossible, or close to impossible, to light your subject from above. You’ll only be able to work with transparent subjects with the 10X or more powerful lens. It’s more difficult to manage the focusing or positioning with the 10X lens. When a professional microscopist uses a 100X lens she/he will usually add oil to the top of the subject and then put the lens into the oil. There’s less reflectivity if you do this. You would only be able to photograph transparent subjects with light transmitted from below the stage. I have not tried to do this, and, unless I find some transparent subject that seems absolutely compelling to me, I am unlikely to try it in the future.

Eyepieces, Shown are a Leitz 6x and 10X and a Wollensak 15X and 20X

One of the things that may not come with a student-grade microscope is multiple eyepieces. And this is one of the things that you might very much want for photo microscopy such as I do. Since it’s so difficult to use more powerful objective lenses, you may find yourself wanting to change the eyepiece to change the power of the scope. Eye pieces come in a variety of strengths. I own a 4X eyepiece, a 10x eyepiece, a 15x eyepiece and a 20x eyepiece, which gives me some variety of reproduction powers. Surplus shed carries a number of different eyepieces and they would be a good place to start looking for eyepieces. A student grade microscope usually comes with a 10X eyepiece and that is a good place to start. Neither standard eyepieces or objective lenses are terribly expensive, compared to camera lenses. There are some special purpose objective lenses if you’d like an upgrade. If you find a PLAN objective lens it will be sharper than the lenses that come with most scopes. The biggest difference might be that an inexpensive objective lens will be more likely to be fuzzy at the sides of your image.

Geared stage

Most student microscopes have clips which will hold down a regular microscope slide. Then you position the slide, or other subject by moving it with your fingers under the scope. This is the biggest problem with inexpensive microscopes. Better scopes have a geared stage to move the subject around under the scope. If you really enjoy photo microscopy you might want to get a scope which has gears to control the position of the subject.

Lowell Pro light with Barn Doors

Lowel Pro light

The next thing you will need is a light source. Most student-grade microscopes and in fact most fancy microscopes only have a mirror below the lens. Most scopes also have a condenser between the mirror and the stage which changes the spread of the light that you’re using. I find that the condenser is not terribly useful to the way I approach microscopy, but you may find it helpful. Some student grade microscopes will not have a condenser. The actual light source that you use can be something as simple as a desk lamp or even the room light. And that will work very acceptably for an awful lot of work that you might do with the microscope. Look for a lamp that has a continuous spectrum or perhaps an LED light source. Stay away from fluorescent light sources because the spectrum can make it very difficult to get a true color reproduction or can change the color reproductions in unexpected ways. I find that I rarely look for accurate color in micro photography, especially because the images aren’t things we can usually see with the unaided eye. Often, I will use the 3200º Kelvin quartz light and either not compensate for the warm color shift of compensate in Adobe RAW when I open the image. A small light source gives you more control than a broad light source. At this point I am using a Lowel PRO quartz light, which provides much more light than any desk lamp. I like this a lot, but it’s not available new, there are generally several of them on eBay pretty inexpensively. Lowel still makes several more powerful quartz lights, like the Lowel Omni or Tota quartz light but these might be too hot for microscope work (they do get extremely hot). A bright light source is especially important when I start to filter or modify the light because I will still have enough light to actually see the subject. Even without a filter it’s dark through a microscope; more so when the light has to go through the camera and into the viewfinder, after it leaves the microscope eyepiece. The next problem is to position the light source. The Lowel PRO quartz light can be attached to a regular light stand mount or it can be attached to a tripod mount. This enables you to use a ball head or another tripod head to position your lamp in relationship to your subject. This light also has barn doors which give you more control over the light. You can also move the microscope mirror which will help position the light; that is if you are lighting your subject from bellow. If you’re using a 4x objective lens you can also light a subject from above, which makes positioning the Lowel PRO light with a tripod head even more helpful. You can also use a strobe to light, even a dedicated camera flash. This can increase sharpness, because camera shake can be a problem, BUT, it’s very difficult to be sure what your subject will look like when you take the picture. Also, you’ll still need a bright light to focus.

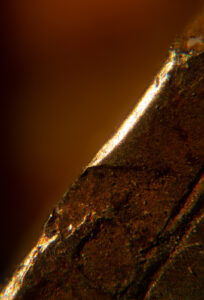

The 4X lens focused on a feather. You have a good amount of room between the lens and the subject.

If you are using the 4X objective lens you will find that most of the focusing can be achieved with the course focus wheel on your scope. The fine focus wheel is useful when you try to use that 10X lens. You will also find that the objective lens will stay at about the same distance from you subjects, so if you get a sense of that distance you can set the scope at about the right distance before you look through the camera. Your actual focus is achieved by looking through the camera viewfinder. Since your microscope is set up vertically, it may help to place the scope on a low table or get something to help you stand above the scope. As you might imagine depth of field, holding things at different distances form the lens in acceptable focus, doesn’t really exist with microscopes. With few exceptions, notably Zeiss Luminar lenses, microscope lenses do not have diaphragms, so there is no way to adjust depth of field, that is if you had any… What you can do is use Photoshop to do focus stacking. In order to do this, you need to take a several pictures at different focus points. Photoshop will enable you to combine these images into a single image with better focus. This can be a very helpful technique. While it is outside the scope of this particular post you will find that there are plenty of tutorials on line. Or, you could wait for me to do a post about modifying micro images in Photoshop. If you do take images for photo stacking, you’ll want to take them at the same exposure.

Image without focus stacking

Image with focus stacking DSC2130

When I first worked with high magnification optical systems exposure was very difficult to calculate. I had to compensate for long bellows extension on the view camera as well as reciprocity failure form the long exposure times. It is still astonishing to me how much easier it is to get a great exposure with a digital camera. If you set your camera on aperture preferred, you’ll get a good exposure. You may want to add exposure compensation correction, if you want a darker or lighter exposure. You might want to see what an image looks like at different settings, just to get a better feel for how you can interpret your subject. Of course, you can also do a lot of interpretation after you capture the image in photoshop. These changes in exposure calculation are perhaps the biggest improvement in micro photography that I’ve seen in 40 years. The massive improvement in the amount of information that a sensor records, compared to 35mm film, is also very significant. I used to do micro photography with large format cameras and transparency film, which was really quite difficult.

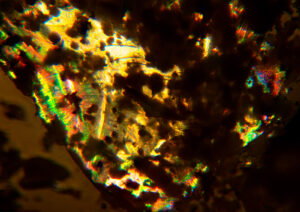

Sodium Thiosulfate

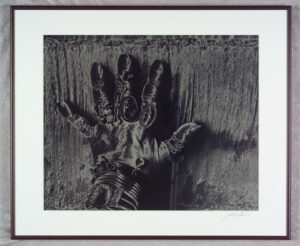

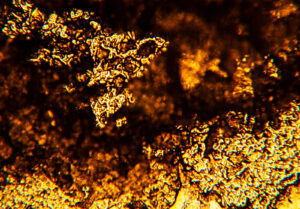

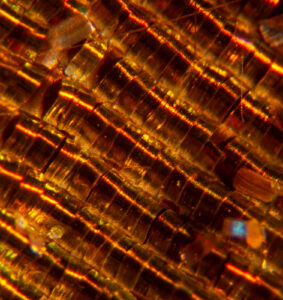

As you look at the pictures of the set-up and the various tools I use, you might want to begin thinking about subjects. I’ve recently done some nice work with old watches and some shiny goo meant for hair. Jerome Russel used to be a client and they made some very shiny hair care products with glitter and other reflective materials. I’ve included shots of both here.

Watch Parts

Old Watch Parts DSC2210

Old Watch Parts DSC2207

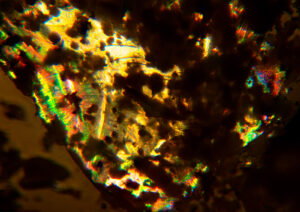

Jerome Russel Hair stuff:

Hair goo-focus stacking DSC2069

Hair goo-focus stacking DSC2061

Hair goo-file heavily modified in Photoshop DSC2058

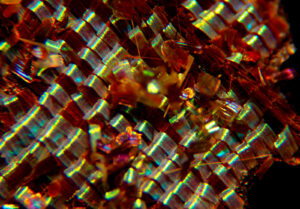

Of course, a lot of things have interesting colors. Below are a couple of shots of dried Selenium toner, which is used in the wet darkroom to add color to B&W prints.

Selenium Toner DSC1999

Selenium Toner-file heavily modified in Photoshop DSC2000

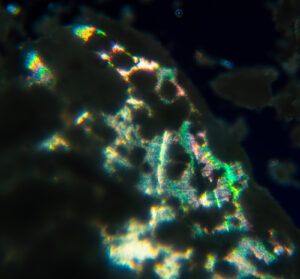

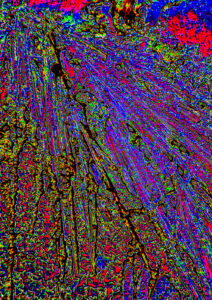

Let’s not forget living things. These are a couple of pictures of butterfly wings. Bet you didn’t visualize them looking like this.

Butterfly wing DSC2050

Butterfly wing DSC2046

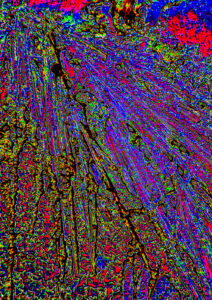

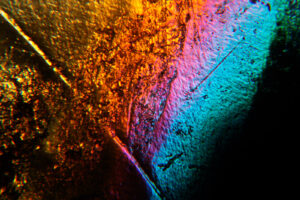

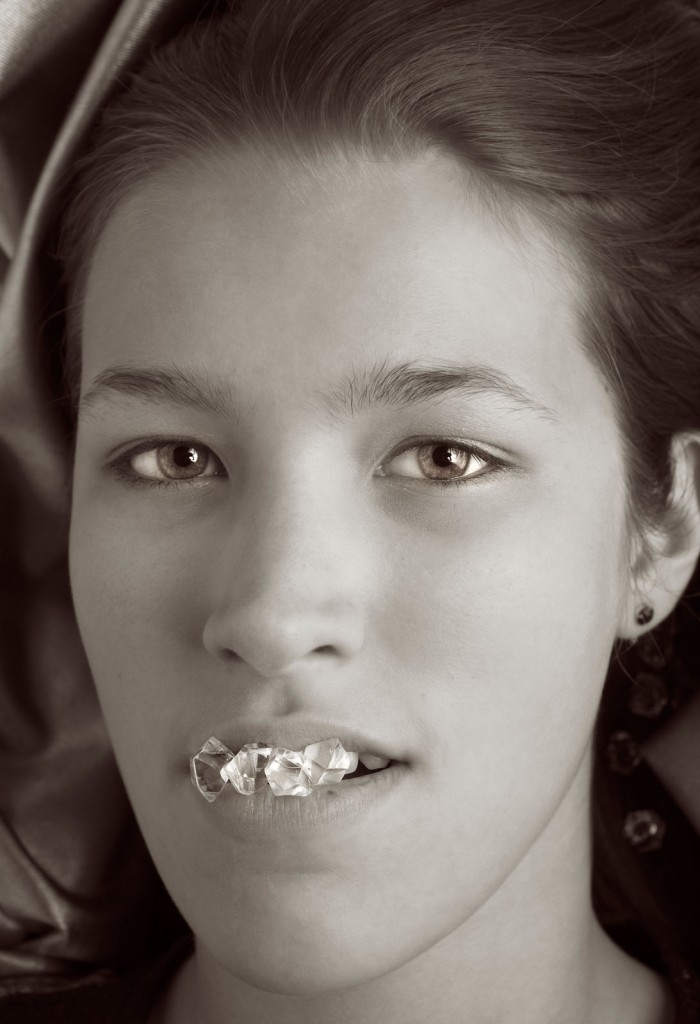

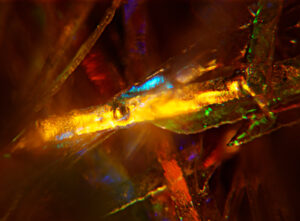

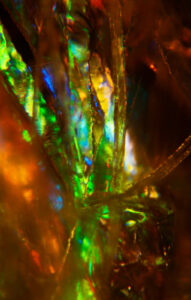

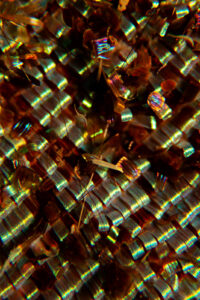

I mentioned filters above. There’s a lot of science behind this trick, but I’m going to cut direct to the chase. Put certain transparent materials, things like plastics and sodium thiosulfate (B&W fixer from the wet darkroom) between two polarizing filters. As you rotate one of the filters colors will start to appear. FUN! But, as I mentioned above, you need a lot of light. These shots are of a plastic prop ice cube. You can get interesting results, but you’ll need to experiment. Frankly all of photo microscopy requires an experimental attitude.

Plastic Prop Ice Cube-Dual Polarization

Sodium thiosulfate, fixer in the B&W darkroom-Dual Polarization DSC2025

As I mentioned at the top of this post, I am now offering prints of many of these images. If the caption has an index code like DSC1234 you can buy a print! Right now, all prints are set to fit on an 11×14 inch piece of paper. If the image is too thin it will have white paper on the sides. I am printing with an archival ink/paper combination. Prints are shipped by USPS priority mail to anywhere in the US that’s covered by Priority Mail service. The price is $75 for the first print and $60 for each additional print ordered at the same time. Please e-mail me at john@siskinphoto.com and include index code and your address. I will send you a PayPal request to arrange payment. I will be adding old and new images to this service. If you see an image on my site you would like to purchase please tell me where you found it and I’ll try to make it available to you. Thanks for your support!

A few links to the items mentioned in the post:

Student scope:

https://www.surplusshed.com/pages/item/T1480D.html

Microscope adapter:

https://www.surplusshed.com/pages/item/M1573D.html

Sony T-mount:

https://amzn.to/3s7xGOa

Nikon T-mount:

https://amzn.to/312M2DC

Canon T-mount

https://www.bhphotovideo.com/c/product/261256-REG/Celestron_93419_T_Mount_SLR_Camera_Adapter.html

And my books!

Understanding and Controlling Strobe Lighting: A Guide for Digital Photographers

https://amzn.to/3tH5Dp9

Photographing Architecture: Lighting, Composition, Postproduction and Marketing Techniques

https://amzn.to/3c8nLlU