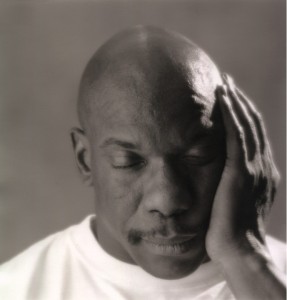

This shot was focused mid-way through the image to hold focus back to front. Shot made with a Toyo 4X5 camera.

Well I hope I haven’t lost too many readers by going on about aperture for three blogs, but it is really important to understand this in order to make good pictures. The idea is that the use of the right aperture allows the photographer to control what part of an image the viewer concentrates on.

The next part of understanding aperture I want to discuss is the hyper focal distance. This is the point at which you focus and stop down in order to create the most depth of field possible in a shot. Of course it is different with different focal length lenses, as we saw last week. Of course it is also different at different apertures. The thing to keep in mind, regardless of aperture and focal length is that in order to maximize depth of field you would not focus on infinity. Two thirds of the depth of field exists behind the focus point and one third in front. You would not be using the depth of field efficiently if you focused on the furthest point that the lens could focus on, something closer would make better use of depth of field. Also if everything in you shot is effectively at infinity then depth of field doesn’t matter.

There is a button on most cameras to help you figure that out, and sometimes it does help. The reason I say sometimes is that this button causes the lens to stop down, and that makes the picture darker, but you can see the depth of field. The darker image in the viewfinder can mean that the image is hard to see, which can make the preview pretty useless especially indoors. Modern cameras are set up to let you look through the lens at its widest opening, which makes focusing much easier. The lens stops down to the working aperture at the moment you activate the shutter, this system works very well. Under the right circumstances, usually bright, the depth of field button can give you an indication of how the depth of field will look.

I promised that memorizing the apertures would be helpful, the reason is that these numbers apply to any time that you are

working with the area of a circle. For instance when working with light. If you have a light at 5.6 feet from a subject and you bring it closer, to say 4 feet that the light on the subject will be one stop brighter. You went from f5.6 to f4, a one-stop increase in light. Similarly if you had a light at 8 feet from a subject and dragged it back to 11 feet from the subject you would lose one stop of light. Wedding photographers used to use manual strobes like the Norman 200B, they would use this principal to rapidly figure changes in exposure. The same principal made it possible to figure bellows extension, but I won’t trouble you with that now.