It’s been a few weeks since I caught up with the blog. There has just been a lot going on. I’ve been trying to get the studio open. I’ve got a new client, and, oh yeah, my wife and I bought a house. I’m cheating this time around because most of this entry is an answer to one of the students in my class: An Introduction to Photographic Lighting . I hope you’ll take this class or one of my others: Portrait Lighting on Location and in the Studio and Getting Started in Commercial Photography. I have to remind you about the books as well.

Anyway, this is a picture of the studio today. My goal is a big empty space, and well it’s big and empty right now. I’ve got utilities, which is important. I also have business insurance. I got insurance from a local broker because it was quick. I’ll be reevaluating my insurance in the next few months. I still need to do an equipment list. The most important thing is to have liability, and that’s covered. The rest of the pictures in this entry are taken with at least one projected light source, which I’ll mention again below.

Anyway, this is a picture of the studio today. My goal is a big empty space, and well it’s big and empty right now. I’ve got utilities, which is important. I also have business insurance. I got insurance from a local broker because it was quick. I’ll be reevaluating my insurance in the next few months. I still need to do an equipment list. The most important thing is to have liability, and that’s covered. The rest of the pictures in this entry are taken with at least one projected light source, which I’ll mention again below.

The problem with the built in strobe on your camera (you can call it a flash if you must) is that it’s right on top of the lens. There are few situations in which your world is lit by a light right over your eyes: miners’ helmets do this and a few flashlights. Still nobody ever said it was good light, just convenient. And because it’s easy to do the camera manufactures put it into your camera. I think the only thing it is good for is flash fill, and there are a lot better ways to do flash fill.

The problem with the built in strobe on your camera (you can call it a flash if you must) is that it’s right on top of the lens. There are few situations in which your world is lit by a light right over your eyes: miners’ helmets do this and a few flashlights. Still nobody ever said it was good light, just convenient. And because it’s easy to do the camera manufactures put it into your camera. I think the only thing it is good for is flash fill, and there are a lot better ways to do flash fill.

It’s extremely difficult to understand how lighting gear compares across brands and types. I’m going to try to explain why. First I’ll mention how light is used, and what  you might want to compare. There are three types of light: hard light, soft light and projected light. The first two are covered extensively in my Introduction to Photographic Lighting class, but I need to mention a couple of things. Projected light isn’t in the class for good reasons. But I will say a few things about it here. Also I’m going to try and attach some projected light shots. Hard light is light from a small source. It acts like direct sunlight: hard shadows and a lot of sparkle. You create this by using direct flash with out diffusers. Because you aren’t using anything to make the light into a larger softer source you can often get by with a strobe that doesn’t have much power, like the built in strobe. You can make very interesting and dramatic light with hard light, but the position of the light is critical. Position is the big problem with the built in strobe. When you make the light source bigger, with a light panel, soft box or umbrella, you’ve lit the subject from more angles, which makes soft light. This softens shadows and makes a smoother transition from light to shadow. An overcast day is soft light: light comes from the entire sky and there are few shadows. Large light modifiers inevitably absorb a lot of your light. In addition they leak light into places you don’t need lit. As a consequence you’ll need more powerful strobes to make very soft light. You should remember that it is the size of the light source that is important, not the type of light modifier. So a 60-inch umbrella will always be softer than a 30-inch umbrella at the same distance from the same subject. A large umbrella and a large soft box give similar light if they have similar surface area. Of course you can have a light is softer or harder depending on the size and the distance from the subject.

you might want to compare. There are three types of light: hard light, soft light and projected light. The first two are covered extensively in my Introduction to Photographic Lighting class, but I need to mention a couple of things. Projected light isn’t in the class for good reasons. But I will say a few things about it here. Also I’m going to try and attach some projected light shots. Hard light is light from a small source. It acts like direct sunlight: hard shadows and a lot of sparkle. You create this by using direct flash with out diffusers. Because you aren’t using anything to make the light into a larger softer source you can often get by with a strobe that doesn’t have much power, like the built in strobe. You can make very interesting and dramatic light with hard light, but the position of the light is critical. Position is the big problem with the built in strobe. When you make the light source bigger, with a light panel, soft box or umbrella, you’ve lit the subject from more angles, which makes soft light. This softens shadows and makes a smoother transition from light to shadow. An overcast day is soft light: light comes from the entire sky and there are few shadows. Large light modifiers inevitably absorb a lot of your light. In addition they leak light into places you don’t need lit. As a consequence you’ll need more powerful strobes to make very soft light. You should remember that it is the size of the light source that is important, not the type of light modifier. So a 60-inch umbrella will always be softer than a 30-inch umbrella at the same distance from the same subject. A large umbrella and a large soft box give similar light if they have similar surface area. Of course you can have a light is softer or harder depending on the size and the distance from the subject.

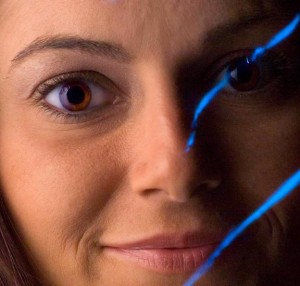

Projected light uses a lens to focus the light, or an image, onto the subject. A simple source for projected light is a slide projector. This article shows how projected light can be used in a shot. There have been very few strobes made that created projected light; one of the few was the Tri-Lite by Norman. I have done some experiments with using strobe for projected light you can see them at my blog: here and here. Projected light can light very small details, but it does require considerable attention to detail.

Projected light uses a lens to focus the light, or an image, onto the subject. A simple source for projected light is a slide projector. This article shows how projected light can be used in a shot. There have been very few strobes made that created projected light; one of the few was the Tri-Lite by Norman. I have done some experiments with using strobe for projected light you can see them at my blog: here and here. Projected light can light very small details, but it does require considerable attention to detail.

You should understand from this that creating good soft light requires considerable power, and the more tools (light modifiers) you can work with the better. Large modifiers, like umbrellas and soft boxes, will fit many different units. Small modifiers, like barn doors and snoots, are usually designed for a specific strobe.

So the next thing to consider is where does the electricity that makes the light come from? If you are using mono-lights then you’ll be using AC power: wall current. The full-power recycling time on your strobes will stay the same all day and all night. If you go where you can’t plug in there are batteries, or you can use a generator. While generators are heavy, you can refill them quickly, which is important for big shoots. Battery strobes are obviously necessary for events, like weddings. They can also be very helpful for architectural lighting because you can hide them and you don’t need power cords. Recycling times depends on how fresh the batteries are, and what kind you use. Manufacturers often lie about recycling times; which makes it tough to compare this critical feature. The basic problem is that batteries put a low limit on the number of shots you can make without more batteries, usually around 200 full power shots. Also extra batteries add weight. There are mono-lights available that have much more power than battery powered units. If you have special needs for battery powered units you might check Lumedyne strobes. They make gear that can be customized in interesting ways.

So the next thing to consider is where does the electricity that makes the light come from? If you are using mono-lights then you’ll be using AC power: wall current. The full-power recycling time on your strobes will stay the same all day and all night. If you go where you can’t plug in there are batteries, or you can use a generator. While generators are heavy, you can refill them quickly, which is important for big shoots. Battery strobes are obviously necessary for events, like weddings. They can also be very helpful for architectural lighting because you can hide them and you don’t need power cords. Recycling times depends on how fresh the batteries are, and what kind you use. Manufacturers often lie about recycling times; which makes it tough to compare this critical feature. The basic problem is that batteries put a low limit on the number of shots you can make without more batteries, usually around 200 full power shots. Also extra batteries add weight. There are mono-lights available that have much more power than battery powered units. If you have special needs for battery powered units you might check Lumedyne strobes. They make gear that can be customized in interesting ways.

There are basically three methods for controlling exposure with a strobe. The first is manual, and if you have time to set-up the lights, this is undoubtedly your best choice. You need to use your eyes to design the light, to perfect it for each subject. If you depend on formulas or auto systems you can easily get a perfect exposure, the right amount of light, but the light may have the wrong placement and balance. The human eye/brain is much better at designing light to fit a subject than any meter. An important goal of my classes is to help you to visualize good light for different subjects. Mono-lights are manual lights. The problem with manual lighting is that it takes time to get it right. The second system is a strobe with a built in meter. These do not use the camera meter; they just specify the aperture the camera should use. They are quicker to use than a manual strobe. Actually these are pretty good and cheap. I use this sort of equipment when I need to shoot an event. The classic Vivitar 283 has this sort of automation, so do a lot of Metz units. I’m using Sunpak 120J units that controls light this way. I’m not sure who makes these strobes currently. Finally there are dedicated strobes that meter through the camera. These are very accurate at creating the right amount of light, although, as noted above, that doesn’t mean the light will be designed well. These units are expensive, considering the amount of power they provide: $550 for a Canon 600EX. Several units can be used together, and still metered by the camera. All of this makes these units very good for weddings and other events. You can use them for other types of lighting, but I don’t think they are the best choice.

There are basically three methods for controlling exposure with a strobe. The first is manual, and if you have time to set-up the lights, this is undoubtedly your best choice. You need to use your eyes to design the light, to perfect it for each subject. If you depend on formulas or auto systems you can easily get a perfect exposure, the right amount of light, but the light may have the wrong placement and balance. The human eye/brain is much better at designing light to fit a subject than any meter. An important goal of my classes is to help you to visualize good light for different subjects. Mono-lights are manual lights. The problem with manual lighting is that it takes time to get it right. The second system is a strobe with a built in meter. These do not use the camera meter; they just specify the aperture the camera should use. They are quicker to use than a manual strobe. Actually these are pretty good and cheap. I use this sort of equipment when I need to shoot an event. The classic Vivitar 283 has this sort of automation, so do a lot of Metz units. I’m using Sunpak 120J units that controls light this way. I’m not sure who makes these strobes currently. Finally there are dedicated strobes that meter through the camera. These are very accurate at creating the right amount of light, although, as noted above, that doesn’t mean the light will be designed well. These units are expensive, considering the amount of power they provide: $550 for a Canon 600EX. Several units can be used together, and still metered by the camera. All of this makes these units very good for weddings and other events. You can use them for other types of lighting, but I don’t think they are the best choice.

I want to talk about the problem with discussing power. You can check out this article, although it isn’t my favorite. Basically a strobe with a built in reflector like a Canon 600EX or a LumoPro can be compared with another strobe with a built in reflector pretty accurately. However mono-lights and studio strobes take a large number of different accessories, even different heads, so you can’t do an accurate comparison between them or between mono-lights or studio strobes and strobes with built in reflectors. Some of the manufacturers of various strobes will inflate their numbers. The article describes how to determine a guide number and what watt-seconds are.

I want to talk about the problem with discussing power. You can check out this article, although it isn’t my favorite. Basically a strobe with a built in reflector like a Canon 600EX or a LumoPro can be compared with another strobe with a built in reflector pretty accurately. However mono-lights and studio strobes take a large number of different accessories, even different heads, so you can’t do an accurate comparison between them or between mono-lights or studio strobes and strobes with built in reflectors. Some of the manufacturers of various strobes will inflate their numbers. The article describes how to determine a guide number and what watt-seconds are.

I just now mentioned studio strobes. Basically these do what a mono-light unit does, but you have to plug the head into a separate pack and then plug the pack into the wall. These are not battery packs: the unit still needs to be plugged into the wall. The packs create the high power spark for the strobe heads. Usually several heads will plug into one pack. These can be very economical to buy used. I have Norman 900 series strobe units, some of which, I’ve used for more than thirty years. Keep in mind that strobes can last quite a long time, so if can make sense to invest in good equipment. We’ll probably still need lights to design better pictures in another thirty years.

I hope people are interested in these posts, but I really don’t know. If you want to leave a comment you have to log in. I’m sorry about that, but I was getting a huge amount of spam posts, so I had to change to registration. If you’d like you can send me an e-mail with your comments, john@siskinphoto.com. Also please remember the classes and the books!

An Introduction to Photographic Lighting

Portrait Lighting on Location and in the Studio

Getting Started in Commercial Photography.