My books and my classes give me a reason to keep doing this blog. If you’re in Indiana I hope you’ll consider taking my Portfolio Workshop. You can see a little more information about this workshop if you check out this blog post . I’ve listed my BetterPhoto classes at the end of this post. Thanks so much for your attention.

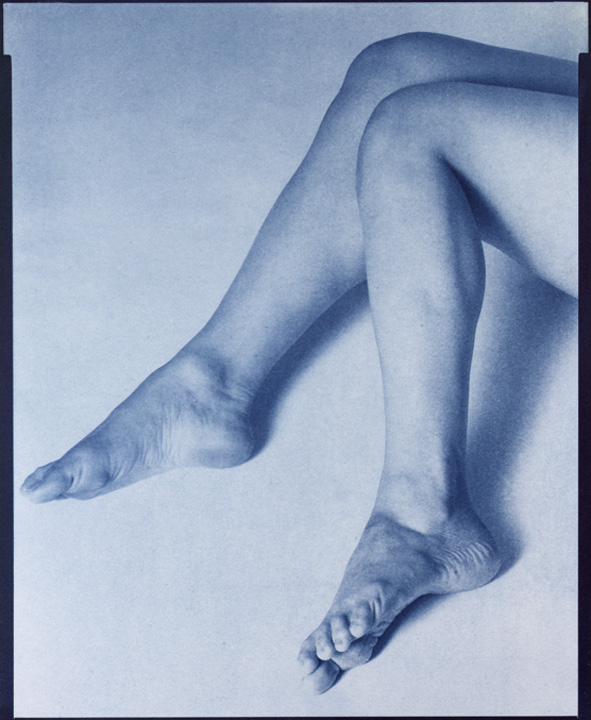

I see as a photographer, constantly breaking the world into still images. I think that most people who spend a big chunk of life doing photography see a little differently from people who aren’t involved in static art forms. I’ll look at something and think: “I’d shoot that, maybe a little warmer and with more contrast” or maybe: “That was a really great instant” and: “Look at that design.” I think this is part of being a good photographer. I once heard a guy say that he always adjusted a TV to look like Kodachrome, since that was the way he saw the world. Of course this illustrates one of the problems with this way of seeing: you start to see everything the same way. I’ve been known to walk by an interesting subject while thinking that’s not the kind of shot I do. I often make my shots warmer, even my black and white shots, but I can’t remember the last time I made a shot cooler.

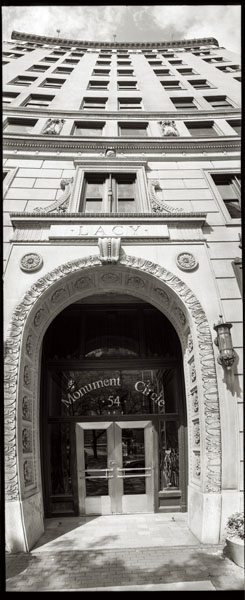

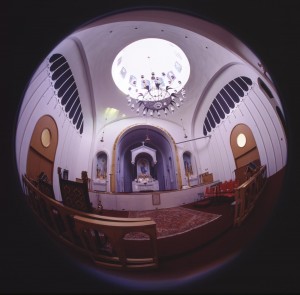

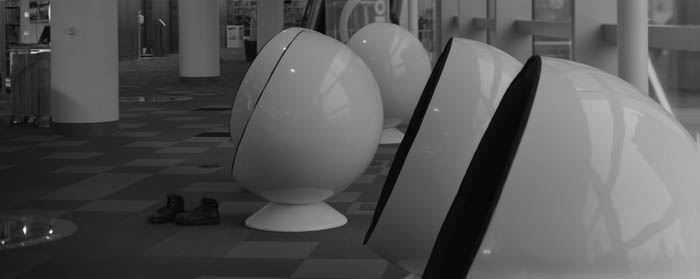

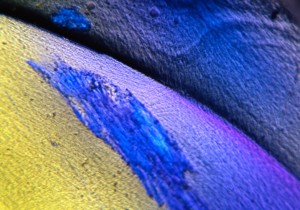

So I’m always looking for ways to break out of my way of seeing. I know that many people want to have a style, but not me. I’m a photographer, not a painter, so I can be prolific and do work that’s new. I want to push myself to see in different ways. One of the ways I do this is to work with different tools: cameras, lenses and software. I just got a Horizon Perfekt, which is really helping me to see differently. This camera shoots a 120º image, horizontally anyway. It’s really different from other wide-angle images because the lens actually moves during the shot.

I shot with a Koni-Omega camera last week. It’s a medium format film camera. This is a manual camera with range finder. Shooting it reminded me of the acronym FAST: Focus, Aperture, Shutter and Think. I think that my digital camera has allowed me to get a little sloppy with technique. Of course shooting with a new camera is not the only way to open yourself to new ways of seeing, but it can be fun as well as enlightening.

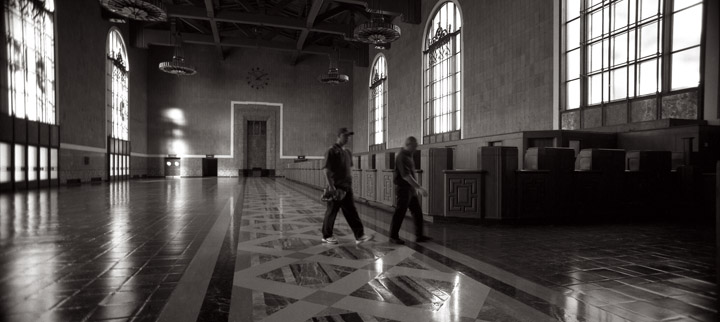

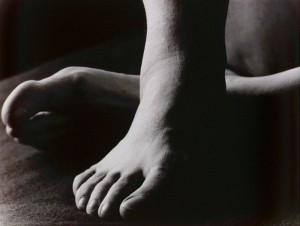

I got an 11X14 camera recently, but I haven’t shot with it yet. I still have to build a lens board and order some film, but it should be a quite an experience. Whenever you work with a very large camera the difficulties increase and so does the expense. But if 11X14 is anything like 8X10 getting a good result will be really fun. Sometimes just getting a good exposure can make you feel great. There’s another practice tool I want to work with. I have an old Spiratone 400 mm f6.3 lens. I’ve really only used it a couple of times because I’m more interested in wide-angle lenses. But in an effort to expand my vision I’m going to put in on the digital camera and start shooting. Who knows how that will affect my seeing? By the way I’ve included a couple of panoramas from the Horizon camera and one more from the Koni-Omega. Also I recently updated my website so you can get an idea of how I’m seeing now. Please check it out at www.siskinphoto.com

Of course there are other ways of expanding your seeing, like taking a BetterPhoto course. Here are the three I teach, perhaps you’d like to take another one or share them with a friend.

An Introduction to Photographic Lighting

Portrait Lighting on Location and in the Studio

Getting Started in Commercial Photography

One other note about BetterPhoto: I’ve been in the habit of sending out a private note to all my former students at BetterPhoto (Almost a thousand people!) each month. There’s some sort of hang up in the e-mail system for thst so, for a while anyway, I won’t be sending that note. I hope no one is too disappointed.

Thanks, John