Usually I put the shameless plugs at the bottom end of this blog, but not this week. My book Understanding and Controlling Strobe Lighting: A Guide for Digital Photographers is on Amazon.com at number 16 in photographic lighting books! And there was much rejoicing! Here is a sample chapter. Of course I still hope that you will consider purchasing my fine art book B Four: pictures of beach, beauty, beings and buildings. Frankly purchases of this book mean a lot to me. I really hope that people will consider this work. And you know that I teach for BetterPhoto.com. I’ll leave those links to the end of the blog.

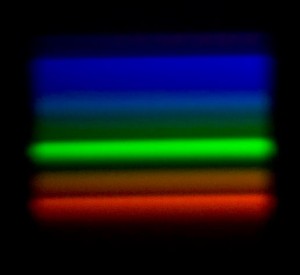

There are a few ways to change the shape of the face. The one I talk about most is with lighting. You can use light to shape the face in a two dimensional medium. The more you use large light sources, particularly the light panel/umbrella combination the less strong shadowing you will have, and the less definition you will get.

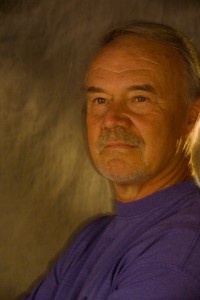

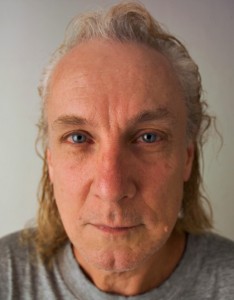

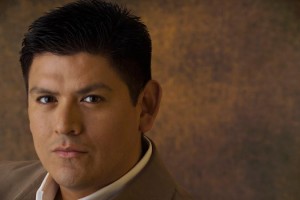

The second consideration is perspective. This really means where you stand. If you are 2 feet from a persons face the contours of the face are exaggerated. If you shoot at 10 feet from a subject the face is flat. Consider it this way, the distance from your lens to the nose is say 24 inches, then the distance to the ear will be close to 29 inches. The difference between these two numbers is a significant percentage of the total. If you are 72 inches (6 feet) from the nose than you will be about 77 inches from the ear, the difference is insignificant. So if you want to make a shot with a flatter perspective you need to move further away from the subject. This will require a longer lens, to keep the subject the same size in the image. On my full frame camera I generally don’t use anything less than a 100mm lens for a headshot of an average face. For a face with extreme contours I’ll use a 200mm lens. Since most people use smaller chips they will need to convert these numbers, but for instance a 50mm lens is pretty short (about 80mm converted) to use for an average face. Perhaps an 85mm lens might be better, for an average face and you might want 135, for an extreme face. In these two shots I used a 50mm lens on my full frame camera and a 200mm lens. The lighting is the same. You can see a difference in the way the face looks. I think he 200mm shot is ok, but the 50 is certainly too exaggerated.

This is why it is important to move your camera rather than rely on a zoom lens when you do portraits. If you’re to close or too far away the zoom won’t fix that it will just change the perspective.

Of course changing the angle of the face can also change the shape. If you shoot a profile a strong nose or chin will be very visible.

Please consider taking one of my classes, or even recommending them. I have three classes at BetterPhoto:

An Introduction to Photographic Lighting

Portrait Lighting on Location and in the Studio

Getting Started in Commercial Photography

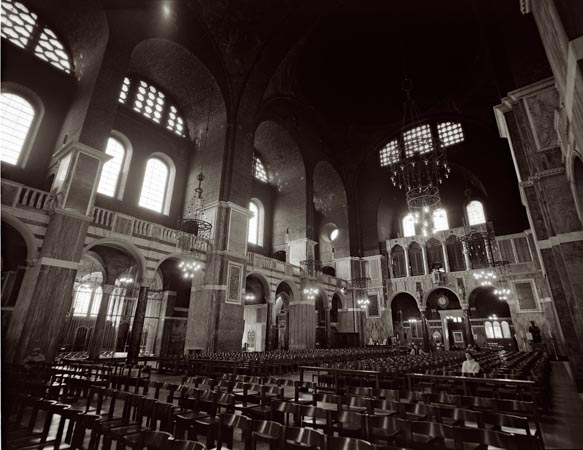

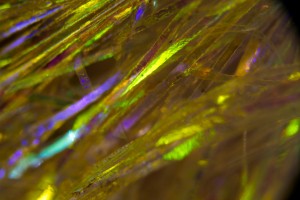

Just a couple more from B Four;

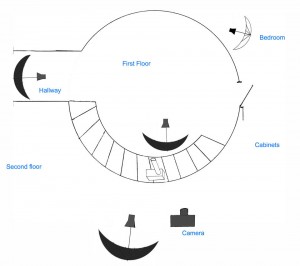

There are a lot of lighting products on the market, and many of them are mostly hype. There are only so many ways you can manipulate light, and few of them are new. So you can make a light source larger with an umbrella, soft box or a light panel. If you want to put light in just one part of an image you will probably need a snoot, grid spot, or barn doors. There are other ways to do these things, but they do about the same things. Changing the name doesn’t change the product much.

There are a lot of lighting products on the market, and many of them are mostly hype. There are only so many ways you can manipulate light, and few of them are new. So you can make a light source larger with an umbrella, soft box or a light panel. If you want to put light in just one part of an image you will probably need a snoot, grid spot, or barn doors. There are other ways to do these things, but they do about the same things. Changing the name doesn’t change the product much.